Pergunta: Se

nada escapa à gravidade de um buraco negro como é possível

que ele emita radiação?

Resposta: De acordo

com o Princípio da Incerteza de Heisenberg,

não podemos conhecer com a mesma precisão a posição e a velocidade de uma

partícula. Quanto maior a certeza acerca da posição maior será a incerteza

acerca da respectiva velocidade e vice versa. Isto significa que existe

sempre uma incerteza associada ao valor do campo em qualquer ponto do espaço.

Essa incerteza pode ser interpretada na forma de flutuações

quânticas do campo. Uma flutuação consiste num par partícula-antipartícula

(fotão-antifotão, electrão-positrão, ...) que se separa por breves instantes,

voltando depois a juntar-se e a desaparecer.

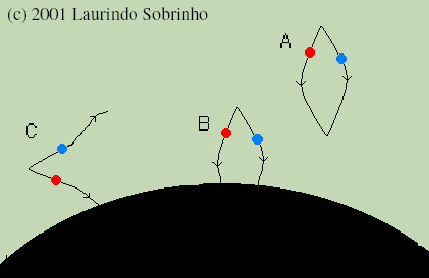

Fig. 1 - Flutuação quântica / Quantum fluctuation

Em cada par uma das componentes tem energia +E e outra energia -E de tal forma que a energia total é zero. Este processo, que está a acontecer constantemente em todos os pontos do espaço, é extremamente rápido pelo que não é perceptível aos nossos olhos. Por isso as partículas envolvidas dizem-se partículas virtuais. Em meados dos anos 70 Stephen Hawking estudou o comportamento destas flutuações junto ao horizonte de acontecimentos de um buraco negro. Na Figura 2 seguinte estão apresentados os vários cenários possíveis.

Fig. 2 - Flutuações junto ao horizonte de acontecimentos

de um buraco negro: A - O par forma-se e desaparece antes de qualquer das

partículas atravessar o horizonte. B - O par forma-se do lado de fora e

ambas as partículas acabam por atravessar o horizonte e C - O par forma-se

do lado de fora e apenas a partícula de energia negativa atravessa o horizonte

Fluctuations near a black hole's event horizon: A - The pair is formed and disappears before any of the particles crosses the event horizon; B - The pair forms outside, and both particles cross the horizon; C - The pair forms outside, and only one particle of negative energy crosses the horizon.

A situação C é particularmente interessante. A partícula de energia negativa que entrou para o buraco negro tem uma massa negativa que será adicionada à massa inicial do buraco negro (que é positiva). Assim a massa do buraco negro diminui. A partícula de energia positiva que ficou do lado de fora não tem par com quem se aniquilar, podendo assim escapar para longe, passando a ser uma partícula real que pode ser detectada por um observador. É neste sentido que se fala de emissão de radiação por um buraco negro ou de evaporação de buracos negros. Este tipo de radiação é designado por Radiação de Hawking. A Radiação de Hawking é tanto mais fraca quanto maior for a massa do buraco negro. Um buraco negro com uma massa comparável à do Sol emite essencialmente fotões rádio (ondas de rádio) muito fracas. Um buraco negro com uma massa de apenas algumas toneladas emite radiação muito mais forte (raios X, raios gama e mesmo partículas como electrões, quarks,...).

Question: If nothing escapes the gravity of a black hole, how is it possible for it to emit radiation?

Answer:

According to the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle, we can't know with full precision the position and velocity of a particle. The greater the certainty about the position, the greater the uncertainty about the respective velocity and vice versa. This means that there is always an uncertainty associated with the value of the field at any point in space. This uncertainty can be interpreted in the form of quantum field fluctuations. A fluctuation consists of a particle-antiparticle pair (photon-anti photon, electron-positron, etc.) that separates for a few moments, then comes together again and disappears (Figure 1).

In each pair, one of the components has energy +E and the other energy -E such that the total energy is zero. This process, which is constantly happening at all points in space, is extremely fast, so it is not noticeable to our naked eyes. Therefore, the particles involved are called virtual particles. In the mid-1970s Stephen Hawking studied the behavior of these fluctuations near the event horizon of a black hole. In Figure 2, the various possible scenarios are presented.

Situation C is particularly interesting. The negative energy particle that entered the black hole has a negative mass that will be added to the black hole's initial mass (which is positive). Therefore, the mass of the black hole decreases. The positive energy particle that was left outside has no partner to annihilate with, so it can escape far away, becoming a real particle that can be detected by an observer. It is in this sense that one speaks of emission of radiation by a black hole or of evaporation from black holes. This type of radiation is called Hawking Radiation. Hawking Radiation is weaker the greater the mass of the black hole. A black hole with a mass comparable to that of the Sun essentially emits very weak radio photons (radio waves). A black hole with a mass of just a few tons emits much stronger radiation (X-rays, gamma rays and even particles like electrons, quarks, etc.).

Respondido por / Answered by: Laurindo Sobrinho (19-06-2006).

Translated by: João Ferreira (16-01-2023).