Foi amplamente noticiado que a Voyager 1 conseguiu sair do Sistema Solar. Há mais de 20 anos que ela não consegue tirar nenhuma foto e a sua memória é apenas um pouco maior do que a de uma calculadora. Que importância ela ainda tem?

A sonda Voyager I foi lançada a 5 de setembro de 1977. Passou pelos planetas Júpiter (1979) e Saturno (1980). Em 1990 a cerca de 40 UA de distância (aproximadamente a distância média de Plutão ao Sol) a Voyager I tirou uma foto da Terra e dos outros planetas. É a foto mais distante que temos da nossa casa. A partir deste ponto a câmera fotográfica da nave foi desativada (dado que a nave não passaria perto de nenhum objeto significativamente grande para que se justifique tirar fotos) e toda a energia restante foi canalizada para os outros instrumentos da nave (diversos detetores, sistemas de comunicação e navegação).

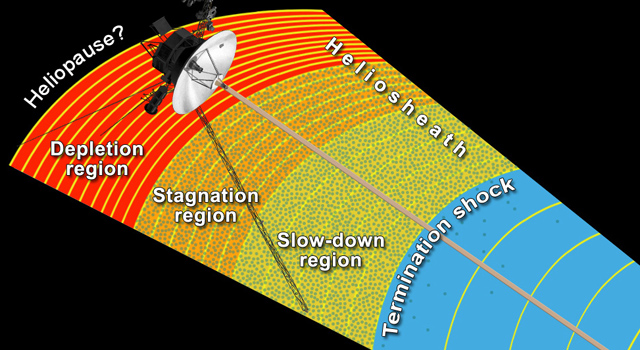

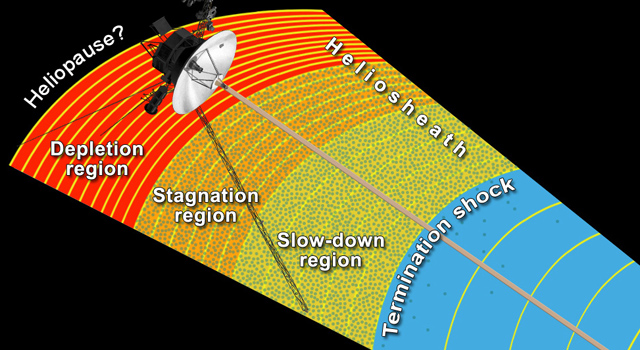

A heliosfera é uma vasta região em forma de bolha que rodeia o Sistema Solar e que se estende muito para além da órbita de Plutão. Esta bolha é mantida do lado de dentro pela pressão do

vento solar e do lado de fora pela pressão do

meio interestelar (ver Fig. 1). O vento solar afasta-se do Sol em todas as direções a uma velocidade supersónica (i.e., superior à velocidade do som). Devido

à interação com o meio interestelar existe um ponto da heliosfera a partir do qual a velocidade do vento solar passa a ser subsónica. Esta região, designada na Fig. 1 por termination shock, foi atravessada pela Voyager I em

dezembro de 2004 quando esta se encontrava a cerca de 80 UA do Sol.

Fig. 1 - Artist concept of NASA's Voyager spacecraft. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech [http://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/news/transitional_regions.html]

Segue-se uma região de transição designada por heliosheath onde a velocidade do vento solar continua a diminuir. Para além disso as partículas

do vento solar são comprimidas e gera-se alguma turbulência. A fronteira exterior desta região (e também da heliosfera) designa-se por

heliopausa. Neste ponto a pressão do vento solar já não é suficiente para empurrar para fora o meio interestelar. A Voyager I atravessou esta região em

agosto de 2012 quando estava a 121 UA do Sol. A Voyager terá energia provavelmente até ao ano de 2025

pelo que até lá continuará a enviar dados preciosos para a Terra (valor do campo magnético, densidade de partículas, etc).

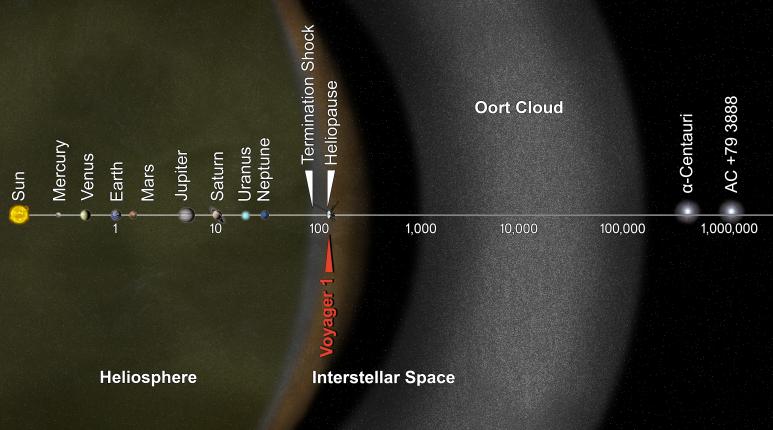

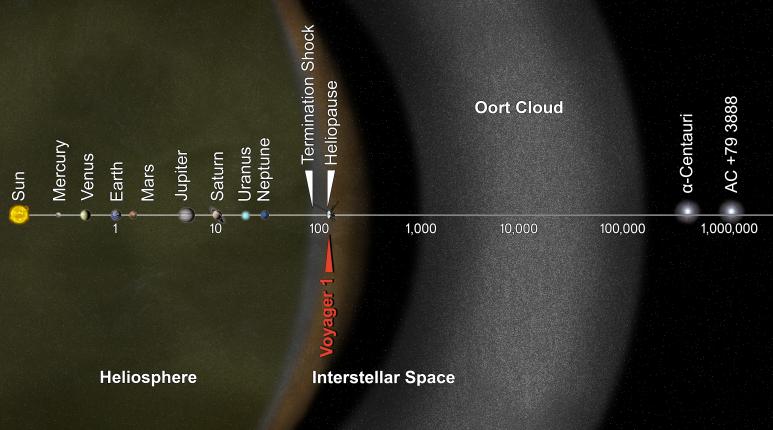

Neste momento a Voyager I está já a 128 UA (ver Fig. 2). Embora navegue já no meio interestelar não será muito correto dizer que já saiu do Sistema Solar. Se considerarmos que o Sistema Solar consiste em tudo o que gira em torno do Sol temos ainda pela frente a

Nuvem de Oort. Trata-se de uma região mais ou menos esférica em torno do Sol composta pelos restos da nebulosa que deu origem ao Sistema Solar. É desta região que são originários os cometas de longa duração. A Voyager entrará nesta região (situada entre 40000 a 50000 UA do Sol) daqui por cerca de 15 000 anos. O próximo objeto do qual a Voyager I se aproximará será a estrela anã vermelha

Gliese 445 (também designada por AC+79 3888). Esta estrela embora esteja atualmente a cerca de 17 anos-luz do Sol está em aproximação pelo que daqui por cerca de 40000 anos estará a "apenas" 3.5 anos-luz do Sol sendo uma das nossas vizinhas mais próximas. Será nessa altura que a Voyager passará "perto" (a 1.6 anos luz de distância) desta estrela.

Fig. 2 - Note-se que a escala representada nesta figura é logarítmica. A distância da

Terra ao Sol é igual a 1UA e por, exemplo, a distância de Saturno ao Sol são

aprox. 10UA, ou seja, numa escala linear o Saturno deveria estar 10 vezes mais

longo do Sol do que a Terra. O mesmo raciocino se aplica aos restantes valores.

De notar também que embora as estrelas alpha-Centauri e AC+79 38888 estejam

alinhadas sobre a mesma linha o que se pretende representar na figura é apenas a

distância das mesmas ao Sol e não a sua localização num espaço 3D. / Note that the scale used in this figure is logarithmic. The distance from Earth to Sun is 1 au and, for example, Saturn is about 10 au away from the Sun, so with a linear scale, Saturn should be 10x further from the Sun than Earth. The same applies to other values. Also note that, although stars alpha-Centauri and AC+79 38888 are aligned with the Sun in this figure, this is purely for distance purposes, and not a 3D representation of the stars' distribution.

(NASA/JPL-Caltech [http://photojournal.jpl.nasa.gov/catalog/PIA17046]).

Os computadores de bordo das sondas Voyager, projetados nos anos 70 do século XX, continuam operacionais ao fim de todos estes anos. Uma vez lançadas as naves não era possível aceder às mesmas para aumentar a memória, trocar de processador ou mesmo de computador (como é recorrente fazermos aqui na Terra!). No entanto

é notável que utilizando esse equipamento obtiveram-se algumas das mais fantásticas imagens

e fizeram-se algumas das mais marcantes descobertas no Sistema Solar!

Para mais informações sobre as sondas Voyager:

http://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/index.html

http://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/timeline.html

http://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/where/index.html

There were many news on Voyager 1 leaving the Solar System. It hasn't been able to take any pictures in over 20 years, and its memory space is only slightly larger than a calculator's. How important is it today?

The Voyager I probe was launched on September 5th, 1977. It passed by the planets Jupiter (1979) and Saturn (1980). In 1990, at about 40 au of distance, roughly Pluto's average distance from the Sun, Voyager I took a picture of Earth and the other planets. It's the furthest picture we have of our home. From this point on, the spacecraft's camera was deactivated, given that the spacecraft would not pass close to any objects significantly large to justify taking pictures, and all the remaining energy was channeled to the other instruments of the spacecraft, like various detectors, communication and navigation.

The heliosphere is a vast bubble-shaped region that surrounds the Solar System and extends far beyond Pluto's orbit. This bubble is maintained by the pressure of the solar wind on the inside, and on the outside by the pressure of the interstellar medium (see Fig. 1). The solar wind is moving away from the Sun in all directions at supersonic speed (i.e., faster than the speed of sound). Due to the interaction with the interstellar medium, there is a point in the heliosphere from which the speed of the solar wind becomes subsonic. This region, designated in Fig. 1 by termination shock, was crossed by Voyager I in December 2004 when it was at about 80 au from the Sun.

A transition region called the heliosheath follows, where the speed of the solar wind continues to decrease. In addition, solar wind particles are compressed, and some turbulence is generated. The outer boundary of this region and the heliosphere is called the heliopause. At this point, the pressure from the solar wind is no longer enough to push the interstellar medium out. Voyager I passed through this region in August 2012 when it was at 121 au from the Sun. Voyager will probably have energy until the year 2025, so until then it will continue to send precious data to Earth regarding the local magnetic field, particle density, etc.

At this moment, Voyager I is already at 128 au (see Fig. 2). Although it already navigates in the interstellar medium, it would not be quite correct to say that it has already left the Solar System. If we consider that the Solar System consists of everything that revolves around the Sun, we still have the Oort Cloud ahead of us. It is a more or less spherical region around the Sun, composed of the remains of the nebula that gave rise to the Solar System. It's from this region that long period comets originate. Voyager will enter this region, located between 40 000 to 50 000 au from the Sun, in about 15 000 years. The next object Voyager I will approach will be the red dwarf star Gliese 445, aka AC+79 3888. Although this star is currently about 17 light-years from the Sun, it is approaching us, so that in about 40 000 years it will be "only" 3.5 light-years from the Sun, being one of our closest neighbors. It will be at that time that Voyager will pass "near" (1.6 light years away) this star.

Computers on board of the Voyager, made in the 1970s, are still operational after all these years. Once the spaceship was launched, it wasn't possible to access them to increase memory space, change the processor, or the computer's model. But it's remarkable that, using this equipment, some of the most amazing pictures were obtained, as well as some groundbreaking discoveries on the Solar System!

For more information on Voyager, see:

http://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/index.html

http://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/timeline.html

http://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/where/index.html